We came to the New Mexico desert to make art: Jean for a silversmithing class, and me to start ghostwriting a memoir for a man whose first name, fittingly, was Art.

Nearly a century before us, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe also came here to create unforgettable, iconic images painted across tablecloth-sized canvases: “a dream landscape, voluptuous, tender, vast,” Roxana Robinson writes Georgia O’Keeffe: a Life.

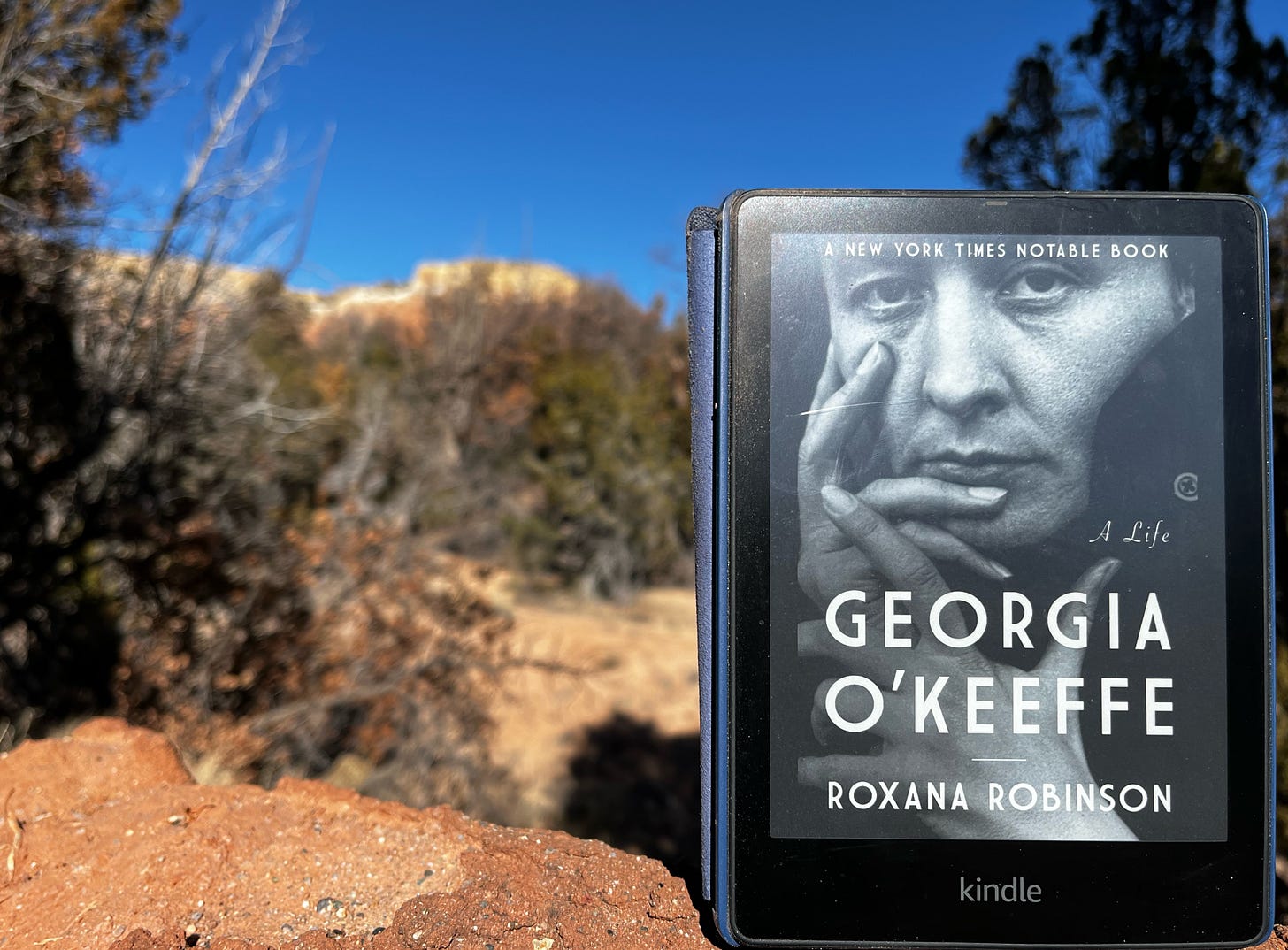

I downloaded a copy of Robinson’s biography on my e-reader and began reading the book the day my foot touched the soil of Ghost Ranch, the remote home to O’Keeffe for most of her life. I’m weird like that. I like to synchronize my books with my life. Sometimes, vice versa.

Georgia O’Keeffe first visited New Mexico in 1917 and, as Robinson tells us, was immediately enchanted by the land: “The pale, clean, quiet adobe town [Santa Fe], the pure, glittering air, and the exhilaration of the high mesa country made the encounter one of great resonance for Georgia.”

I might as well spill my True Confession up front: I have been indifferent to O’Keeffe and her art ever since I saw her first cow skull four or five decades ago. I’ve spent a lifetime of unappreciation. Those big close-ups of flowers, carrying whiffs of eroticism? Did nothing for me. Those animal skulls sprouting flowers and floating midair over deserts? Blasé. If I’m being honest, I couldn’t see what all the fuss was about.

That changed when I started reading Georgia O’Keeffe: a Life and entered the gates of Ghost Ranch (overhung with a cow skull), almost simultaneously. During my two-week stay at the ranch near Abiquiu, New Mexico, I not only came to appreciate O’Keeffe’s, I came to love it (or at least, as the kids say these days, I “started to develop feelings for the paintings”).

I’ll turn it over to the diary at this point, interspersed with some choice quotes from Robinson’s biography. (And, because there is so much text and photos—and because this blog isn’t as big as an O’Keeffe canvas—I’m going to break it into two parts.)

January 5, 2025: We arrive at Ghost Ranch in mid-afternoon. This is Georgia O’Keeffe territory. These are her landscapes, this is her home. We pass under a wooden arch with a suspended Welcome sign swinging in the breeze, complete with a proper O’Keeffe cow skull. The road to the ranch is rutted and washboarded; all the metal inside Sugar the van jingles a merry tune as we roll along.

Georgia first visited Abiquiu (which means “very beautiful”) in 1929, returning in 1931 and starting a pattern of half a year in New Mexico and half a year in New York with her husband Alfred Stieglitz, also a renowned artist, photographer and gallery owner. Alfred never cared for the desert and left it to Georgia while he remained in New York. Year after year, “she returned to the landscape that would nourish and sustain her for the rest of her life,” Robinson writes. Soon after Alfred died, Georgia moved to this country permanently.

“It was the shapes that fascinated me,” she said, “the shapes of the hills.”

As I drive Sugar along the dirt road, we crest a rise, hook a turn between foothills on the downslope and there it is: the ranch, its buildings strung around a large field (ripe for a polo match or a rodeo, depending on the crowd). The field is circled by a dirt road and lined with a corral, bunkhouses, dining hall, arts studio, paleontology museum, guest lodging, and a small stone building labeled “Georgia O’Keeffe Cottage: Private, Please Do Not Enter.”

Jean and I check in at the ranch’s Welcome Center, where we are welcomed nicely and, to my surprise, I’m given a wristband for meals, too. This was unexpected. I’d thought only Jean got meals during her class. In preparation, we’d stopped at the grocery store in Santa Fe and stocked up before coming here. Now what will we do with all this food in the refrigerator?

To top it all off, the meals at Ghost Ranch are pretty darn good. Jean thinks they’re “not good.” She thinks I should reconsider my vote. [Update one week later: Jean was right, I was wrong: the food here is most definitely “not good.” As the days wore on, the food somehow, incredibly, grew worse. In fact, it became offensively bad. Some nights, after surveying the steam table, Jean and I would just do an about-face, return to the van, and eat a cold meal of mixed nuts, cheese, and yogurt.] One nice thing I’ll say about the dining hall: its napkin holders bear poems by Ta-na Hesi Coates, Mary Oliver and Dr. Seuss.

We are given our choice of sites at the RV camp which is mostly deserted this time of year. We see only one other campervan gleaming white through the sage and juniper pines. Later, we discover it’s one of Jean’s fellow silversmithing students who has driven here from Canada.

It’s crisp-cold at night, bordering on biting-cold, and neighboring on gnawing-cold. We keep Sugar buttoned up with the insulated shades snugged against the windows and the furnace cranked to 68 degrees. We have enough propane; we’ll make it through.

January 7, 2025: We’d been up for two hours this morning—still buttoned-up inside, reading and sipping coffee—when I finally slid open Sugar’s side door.

“Ho-ly Christmas!” I breathed sharply.

For indeed, Christmas snow—belated though it may be—had arrived overnight. The campground was blanketed with two fluffy inches: light, moist stuff that quickly made a gumbo of the red earth.

I drove carefully to the dining hall, where we enjoyed a horrid breakfast before driving (equally carefully) through the slick mud up the hill to the studio/classroom where Jean spends her hours—up to nine on some days—while I sit in the van outside working on this ghostwriting project.

The work is going steady, but slower than I’d hoped. It’s not easy “creating Art.” The 120 pages of notes about his life are, to be polite, scattered and tattered. There is nothing chronological about what I’ve been given. I’m trying to put his life in order, but it’s exhausting going back and forth across his pages of notes. Jean’s inside bending silver with a torch-flame, but I’m in here unable to bend any words to my will.

I wonder if Georgia’s paint ever went dry on her brush.

For a break, I take a short hike up the Kitchen Mesa Trail, as far as the dinosaur quarry, to get more pictures of the cliffs wearing white jackets of late Christmas snow. The air this morning is quiet, cold, solemn. Dare I say “holy”?

In 1947, paleontologists visiting this site learned this blood-red clay had also been a graveyard of Coelophysis bauri—small, fast, bipedal predators that looked like tiny T-Rexes. Their ferocious bones are mostly gone now, housed on shelves in a museum back on the main ranch grounds.

Jean and I had hiked up here the previous evening just before dusk, at Golden Hour when all the magic happens. Then, the Entrada sandstone had glowed like a paper-bag luminaria: a rich orange-red-yellow color that shone out, bright as paper bags, against the darkening sky.

Now, those same cliffs had donned formal wear—a bridal white, an ivory tuxedo. Same cliffs, different personalities in the same twenty-four hours.

I come back to the van, refreshed by the cold-air hike, andf dive back into the memoir, patiently arranging the puzzle pieces of this man’s life. It’s tiring work, but I stay behind the plow for the rest of the afternoon. After two hours, I’m ready to say, “I give up.”

Just then, Jean opens the sliding door, slams it shut, throws a fistful of jewelry on the bed and announces, “I give up!”

I close my computer, swelling with concern. “What’s wrong, hon?”

“I’m awful and nobody’s helping me get any better!”

“I don’t think it’s all that bad, is it?”

“It is!” She goes on to describe how the class was moving right into the more complicated overlay technique even though it’s only the second day and how everyone else was doing so much better because they’d all been to a silversmithing class or an earlier session at Ghost Ranch and—surprise, surprise!—Jean was the only silversmithing virgin in the class and it shows, just look at this crap [picking up pendant, then dropping it in disgust], this stupid overlay piece that she kept trying to get right and kept cutting it down more and more and now just look at it, and it’s all too hard and she struggles to get even one of the three teachers’ attention and she’s way over her head in this class and to hell with it all, we should just go, leave first thing in the morning.

When she takes a break from the flagellation, I pick up the pendant. She’s right; it’s sloppy and shows the stress of being overworked, but it doesn’t totally suck. Why not just finish this and move on to the next piece? Sometimes art has to be set aside, and we must forgive ourselves. Maybe the next piece will be easier and better.

Jean sits up in bed, cooling down and taking a second look at things. She picks up the pendant. “It still sucks,” she says.

“Of course,” I reply. “But the next one might not.”

As per her lovely stubbornness, Jean is now determined to finish this sucky overlay pendant to the end. Which, now that she looks at it, might just need another hour or two of work. It won’t be great, but it would be finished. And maybe if she really corralled one of the teachers and got their full attention on her struggles, maybe it might be worth it. Staying in the class, that is.

(Spoiler alert: She did, and it was. Worth it, that is.)

January 8, 2025: I’m hiking the Box Canyon Trail, red-dirt road snaking between the walls of Entrada Sandstone that rise before me. Dark-eyed juncos guide me down the path, not saying a word—not a chirp from any of them. They fly ahead, low to the ground, sewing loops through the air, beaks needling the way. When I pause on the path, they pause in the bushes. When I walk, they flit. I feel welcomed in their world.

I leave the open country, head toward the wrinkled folds of the cliffs. This landscape—how can I describe it?

I won’t. I’ll let Roxana Robinson paint the picture:

It is a lean, bleached, wild place, uneven, full of bluffs and steep canyons. In spite of its aridity, its spareness, there is an overriding softness to it because of the fine sandy soil. The shapes of the hills and the bluffs are gentle, rounded, smooth, and the sense of the dry, powdery soil prevails.

About ten miles north of Abiquiu the landscape begins to alter. The low irregular ridges, covered with scrub, give way to smooth, strange red hills and high pink cliffs. The landscape opens up, and great vistas stretch out to distant purple mountains.

It is not gentle country. The place demands solitude, an intense attention to the land.

I walk softly up the Box Canyon Trail. I watch for the juncos. I pay attention.

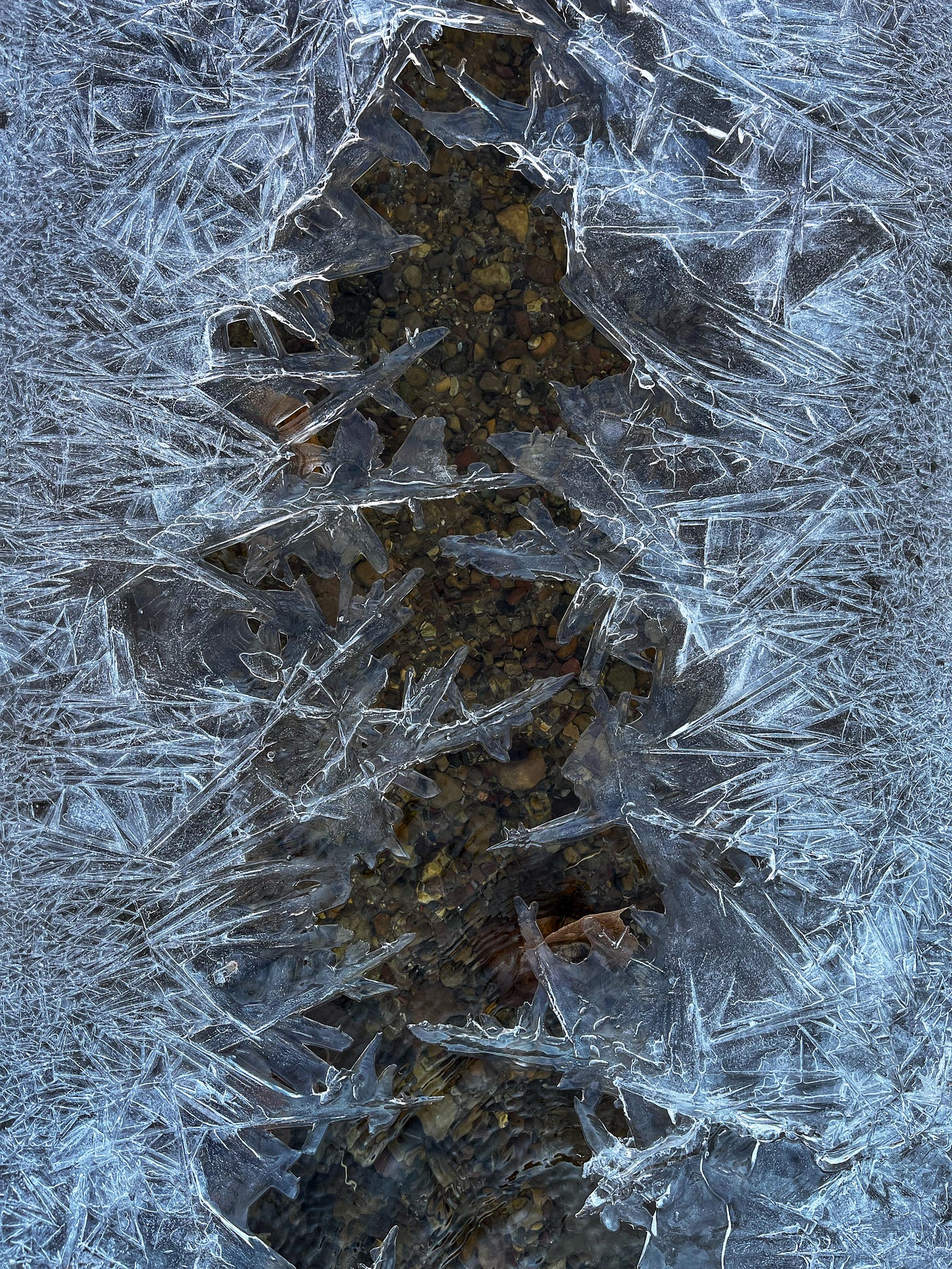

Farther along the trail, I come across snowmelt which gathers and trickles into a thin creek at the bottom of the canyon’s V. With the earlier snow, the stream has surged to life. Underneath a lacy cover of ice, it burbles, it gurgles, it rides giddy-up merrily down the creekbed. I stop to look at the ice. It’s making a creaky, crinkly sound: small ice crystals snapping and popping, like someone repeatedly squeezing cellophane. Meanwhile, the stream flows, tinkly and sweet, just beneath. I want to get this on video with my iPhone, so I crouch.

But I must wait while a jet passes overhead. I want to capture the tranquility of this moment, and there’s no way my phone’s camera will pick up the delicacy of the breaking ice from beneath the great sky-swallowing roar of the jet. I wait and I wait. The jet slow-crawls between clouds. I count to seven, then I count to fifteen. Finally, the last howling engine of man dissolves in the wind and it’s just me and the music of the creek again. I inhale, hold my breath, press RECORD. I preserve thirty seconds of the crackling stream on film, then I move on up the trail deeper into the canyon’s silence.

(Part Two coming soon….)

My own true confession: I was born in NM and have been returning to visit for more than 50 years. But I, too, wasn’t a Georgia O’Keefe fan so I’d never visited the museum in Santa Fe. We had a little extra time at the SF Literary Festival last month & the O’Keefe museum is nearby. So, no excuses this time - and it’s a lovely museum! Well-curated and full of beautiful work. Highly recommended, even if it’s pricey compared to other SF museums.

It’s good to see a post from you. I’ve been wondering about you and Jean and your traveling companions.