If you want a small taste of what the American hellscape will look like for women in the next four years, peek inside Hollow, Bailey Williams’ account of serving as a female Marine for three years during which time she endured taunts, threats, and dismissal—not to mention the rape and sexual abuse which we’re sadly braced for from Page 1. The toxic bro culture is horrific here, but it’s still in its mostly unchecked form during the early 2000s when this memoir is set; just wait until male servicemembers go off the leash under the auspices of Project 2025. There will certainly still be Good Men who stand up for women, but I fear the alarming freedom all the assholes of the world are about to be handed during the Trump administration’s full-on war against women, coming to a home near you in 2025. Strong as she is, I don’t know if even Bailey Williams would have survived a MAGA military.

But survive, and triumph, she did. Bailey’s story is painful to read—but it’s a pain we should all sit with, squirming beneath the ache of rejection, groaning against sexism, and screaming with all our rage as we vicariously watch the sexual assaults which happen again and again on these pages. And then, finally, we may weep with grief as Williams turns inward, transmogrifying her pain into an eating disorder, coupled with long, punishing runs along the California coastline where she lived while serving as a linguist in Monterey.

I had the privilege of reading an early copy of Hollow and here is what I said about it:

Hollow is a flare of pain, a throat-aching cry of rage, a wake-up call at 2 a.m., a sharp splinter slipping under the skin into the bloodstream and traveling to the heart, a rumble in the stomach, and a restless chase after self-identity. Bailey Williams' story of her struggle as a female Marine with an eating disorder will have you riveted to the page and leave you reeling with empathy. This is an astounding book about pain and the empowerment that rises out of it.

Here’s the publisher’s blurb about the book:

At eighteen, Bailey Williams bolted from her strict Mormon upbringing to a Marine recruiting office to enlist as a 2600—a military linguist. But the first language the Marine Corps taught her wasn’t Arabic, Farsi, or Dari. It was how Marines speak to, and about, women. There are only three kinds of women in the Marine Corps, she was told: you can be a bitch, a dyke, or a whore. Determined to prove she’s not whatever it is the men around her believe a woman to be, Private Williams turned to an eating disorder, intending to show her discipline through the visible testament of bone. She ran endurance distances on an increasingly Spartan diet, shoving through her own body’s resistance. Pushed to the brink by a leadership and a culture that demands women shrink themselves, she finally looked to the women around her, and began to wonder what else she was losing. Quietly but inexorably, the power of other women’s stories whispered an alternative path to what it means to be a woman, and a warrior.

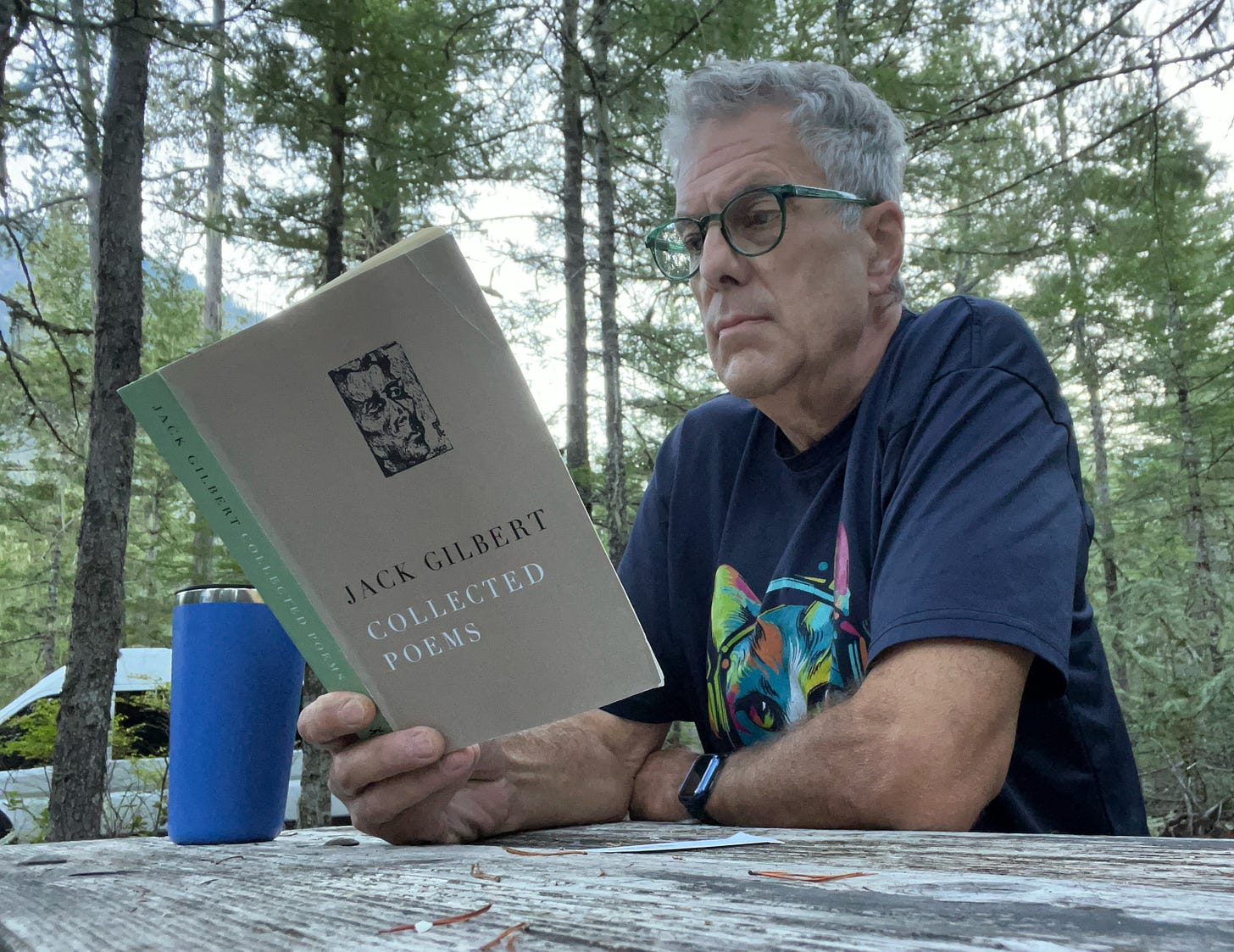

BONUS: I’ve just finished reading The Collected Poems of Jack Gilbert, which I purchased at Iconoclast Books in Hailey, Idaho near the start of our road trip (which now seems like it was oh so long ago!). I’d been hearing about Gilbert for years, but had never read anything by him before picking up this collection. He’s a sometimes difficult poet to parse, but when he lands, he really sticks it. Here are some of my favorite lines from his poems which landed in my Commonplace Book over the past few months:

We are spirits housed in meat,

instantly opaque to the Lord.

(“Angelus”)

I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

But just coming to the end of his triumph.

(“Failing and Flying”)

Take your heart

in both hands and squeeze

out darkness.

(“May I, May I”)

There is a wren sitting in the branches

of my spirit and it chooses not to sing.

It is listening to learn its song.

(“Trying to Write Poetry”)

Poem, you sonofabitch, it’s bad enough

that I embarrass myself working so hard

to get it right even a little,

and that little grudging and awkward.

But it’s afterwards I resent, when

the sweet sure should hold me like

a trout in the bright summer stream.

There should be at least briefly

access to your glamour and tenderness.

But there’s always this same old

dissatisfaction instead.

(“Doing Poetry”)